Michael Strahan’s path to Hall-of-Fame started in Houston

Through the sacrifice of his parents and devotion of his uncle, Michael Strahan discovers what it takes to reach the top

Through the sacrifice of his parents and devotion of his uncle, Michael Strahan discovers what it takes to reach the top

By John McClain

Turn on the television almost any day of the week and watch Houston native Michael Strahan co-hosting "Live with Kelly and Michael," contributing to "Good Morning America" and making his weekly appearance on "Fox Sports Sunday" during the NFL season.

Life has become an around-the-clock, coast-to-coast adventure for Strahan, the former Texas Southern All-American whose 15-year career as a defensive end with the New York Giants has led him to the threshold of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Strahan, 42, and six other members of the class of 2014 will be inducted Saturday night in Canton, Ohio.

"I normally look back and go, 'How in the hell has this happened?' " Strahan said during a recent break in his busy schedule. "You come to a time when you go, 'How do I deserve this, and why is this happening to me and not somebody else?'

"At some point, though, you have to stop questioning it and just go with it. Life's about unexpected things and how well you respond to them. And this was definitely unexpected."

Strahan has become a multimedia star whose popularity transcends age, race and gender because of his irresistible smile, charismatic personality and boundless energy.

"Hey, I'm nervous when I'm on TV - I really am," he said with a laugh. "I'm probably going to be more nervous (Saturday) because this is the highest honor I could get in football. I'll be sweating like a farm animal."

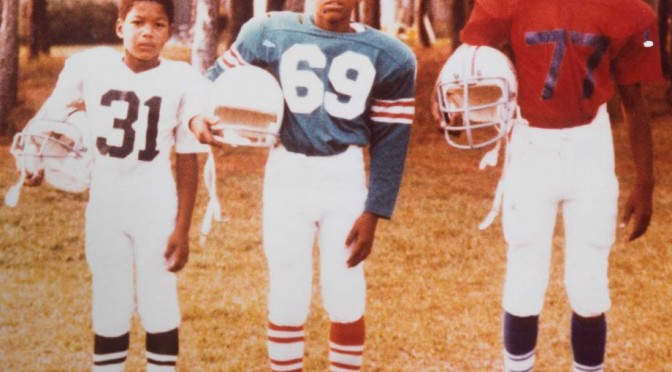

On those rare occasions when Strahan has time to relax and reflect, he still can't believe how a tall, timid 17-year-old with a gap-tooth grin learned to play football in his uncle's front yard in southwest Houston and somehow wound up in the Hall of Fame as one of the greatest players in NFL history.

"Sometimes you get so trapped in thinking, 'I'm so busy and doing so many things,' and you kind of go, 'Oh, OK, it's the Hall of Fame,' " Strahan said about being elected in his second year of eligibility. "It's something else that gets added onto the plate. But when you see the response from everybody, it makes you see how big this really is and how much of an honor it is. I'm very excited."

About 50 members of Strahan's family, many from the Houston area, will be at his enshrinement. Some played significant roles in helping him ascend to where he is today - an A-list celebrity who's engaged to Nicole Murphy, ex-wife of Eddie Murphy, and in demand from New York to Los Angeles.

Of family members sitting in the audience in Canton, none will be more proud of Strahan than his mother, father and uncle.

Returning to Houston

Louise and Gene Strahan, who reside in Spring, raised six children, four sons and two daughters.

Gene, a former boxer, was a major in the U.S. Army. Louise, a basketball coach, also was a good athlete. They moved to Germany when Michael was 9.

"When we were in Germany, Michael kind of grew into football," Gene said about his youngest son. "When he was 15, it's like he just popped up overnight."

As Michael grew, Gene started to think about the possibility of his son earning a scholarship to play college football.

"Michael had talent, but I thought it would be wasted if I didn't get him back to Houston," Gene said. "I wanted him to get a season of high school training and see what happened."

Gene had just the person to take in Michael, teach him the game and serve as a father figure - his brother, Arthur Ray Strahan.

Art - or Uncle Ray to family members - played defensive end at TSU as well as for the Oilers and Atlanta Falcons.

"One of the things I kind of questioned was would Michael have the courage to deal with it?" Gene said. "He was easygoing, and his speed and strength - and his courage - were deceptive."

Michael didn't want to leave his parents, but he knew better than to question their authority.

"My dad had told me he thought I was good enough to get a football scholarship," Michael said. "I'd only played football a year (in Germany), but he told me to do it, that I was good at it, and I believed him."

His parents gave him advice before he departed for Houston.

"I hoped he'd remember what we instilled in him and remember what he was going there to do," Louise said. "A lot of kids leave home and get into trouble.

"In a way, Michael had been sheltered. Coming back to the States was cultural shock for him."

Homesick and scared

The plan was for Strahan to move in with Art's family, play a senior season at Westbury in the fall before returning to Germany to graduate from his private academy.

"Man, I was scared to death," Michael said. "I was homesick for my mom and dad. It was extremely tough. Nothing was natural.

"I never thought I could (play high school football). I had to figure it out as I went. I thought I was just a guy on the field to take up space, but it was because of my lack of knowledge more than anything else, and not my desire."

Michael spent a lot of time on the telephone with his parents.

"He'd call us and tell us he was ready to come back home to Germany, and I'd tell him, 'Son, you are home,' " Louise said.

After his one season at Westbury, Strahan returned to Germany to graduate from his private academy - in a class of two - before returning to Houston for good.

Uncle Ray's tough love

The making of Michael Strahan into a football player is a fascinating story about desire, discipline and tough love in his uncle's front yard.

Art Strahan went old school on his nephew.

"My brother thought Michael was too young, but I said, 'Gene, I'll handle him. I won't hurt him mentally or let him get hurt,' " Art said. "I told Michael it was going to be difficult to get an opportunity (for a scholarship), but he'd have a chance if he followed my instructions and stayed out of trouble.

"It was a whole new world for him in America. He was quiet when he wasn't with his family. He was timid. He'd never played (organized) football. I told him, 'Michael, you've got to suck it up. If there's no pain, there's no gain.' "

The uncle and his nephew worked in the summer heat and humidity.

"He was going from one level to another, and I used to get him in my front yard and beat him up just like he was in the NFL," Art said. "I had to make him mentally tough.

"I had to develop an attitude where you had a right to get tired, but you didn't have a right to quit. I didn't want to give him an excuse for failure. I told him, 'Michael, you've got to kill the will of the man across from you because pain don't discriminate.' "

Looking back, Strahan said he never had a coach at any level of competition who was tougher than his uncle.

"I remember Uncle Ray taking me in the front yard and slapping me around and showing me all different kinds of techniques and not taking it easy on me," Michael said. "Without my dad being there, he was like a father to me.

"Seeing him and Aunt Jean on an everyday basis got me through it."

Art takes a lot of pride in what his nephew has achieved on and off the field.

"Michael's the total package, a perfect example of what the NFL represents," Art said. "My pride in what Michael's accomplished can't be put into words. Michael has never forgotten where he came from, and he never will. I'm so thankful that he stands out like a shining star."

On the mantle above his fireplace, Art has a framed, autographed picture of Michael tackling Green Bay quarterback Brett Favre to set the NFL single-season sack record of 22½ in 2001.

"Uncle Ray, thanks for all the lessons in the front yard," Michael wrote. "They have paid off."

But all that hard work resulted in a lone scholarship offer to Cisco Junior College.

Then Strahan's life changed when his uncle took him to TSU to meet coach Walter Highsmith.

Growing up at TSU

Like Art Strahan, Highsmith knew what it took to play in the NFL. He also played for the Oilers, as did three of his assistants - C.L. Whittington, Conway Hayman and Al Johnson.

Highsmith accepted Strahan as a walk-on and placed him at tight end.

"I didn't even have any film on him, but I knew he had good bloodlines," Highsmith said. "I soon realized he wasn't a tight end, that he belonged on the defensive side of the ball, so we moved him.

"Michael was a workaholic, and I worked the hell out of him. He was gifted, and he wanted to be good. The harder he worked and the more he learned about the game, the better he became.

"I told Michael, 'Wherever you go, don't you let anyone outwork you,' and he hasn't. No matter what he's done, he's always wanted to be the best at it."

Strahan worked hard to get a scholarship.

As a junior, he became one of the Southwestern Athletic Conference's best players with 14½ sacks. As a senior, he became one of the best players in the country, posting 32 tackles for loss and 19 sacks.

Strahan is passionate about TSU and appreciative of the role his college played in his development as a player and as a young man. He donated $100,000 to help the school's famed band, the Ocean of Soul, join him in Canton. He has contributed to other fundraising efforts at TSU, and his generosity will continue.

"At TSU, I grew from a boy to a man in a lot of different ways," Strahan said. "I didn't know anything when I got there, and I was around all these guys who were big and tough and strong and fast and grew up playing football. I had to grow up really fast.

"I didn't get swallowed up by the size of the school. I wasn't just a number. I felt like I was a human being. That was important for me getting acclimated to living in the U.S. after being gone for so long."

Strahan helped put together a recent roast of Highsmith, who resides in Alvin.

"He was a tough coach," Strahan said. "He was always pushing you past where you thought you could go, always making you find that next gear to reach that next level.

"That made it easier for me once I got to the Giants. I'd been pushed as hard as I could be pushed, and I knew I wouldn't crack under pressure."

Induction excitement

Washington Redskins senior vice president of communications Tony Wyllie, a Houston native who worked for the Texans, was a classmate of Strahan's at TSU. They have been friends since they met on campus.

"The whole campus is buzzing about his induction," Wyllie said. "He loves TSU and does so much for the school."

The Strahans had a draft party at Art's house in 1993. Family members, friends and media were invited.

"I remember the night before the draft when I ran into Michael at a 7-11," Wyllie said. "It was a funny scene watching him stuff himself into a green Ford Fiesta.

"You know, I'm pretty sure that's the last time he owned a tiny car like that."

Now Strahan can afford any kind of car he wants and as many as he wants.

"He comes from very humble means, and he's reached the pinnacle of success," Art Strahan said. "He sets an example that if you do it the right way, success can be beating down your door."

25 Jul

2014

By John McClain

Turn on the television almost any day of the week and watch Houston native Michael Strahan co-hosting "Live with Kelly and Michael," contributing to "Good Morning America" and making his weekly appearance on "Fox Sports Sunday" during the NFL season.

Life has become an around-the-clock, coast-to-coast adventure for Strahan, the former Texas Southern All-American whose 15-year career as a defensive end with the New York Giants has led him to the threshold of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Strahan, 42, and six other members of the class of 2014 will be inducted Saturday night in Canton, Ohio.

"I normally look back and go, 'How in the hell has this happened?' " Strahan said during a recent break in his busy schedule. "You come to a time when you go, 'How do I deserve this, and why is this happening to me and not somebody else?'

"At some point, though, you have to stop questioning it and just go with it. Life's about unexpected things and how well you respond to them. And this was definitely unexpected."

Strahan has become a multimedia star whose popularity transcends age, race and gender because of his irresistible smile, charismatic personality and boundless energy.

"Hey, I'm nervous when I'm on TV - I really am," he said with a laugh. "I'm probably going to be more nervous (Saturday) because this is the highest honor I could get in football. I'll be sweating like a farm animal."

On those rare occasions when Strahan has time to relax and reflect, he still can't believe how a tall, timid 17-year-old with a gap-tooth grin learned to play football in his uncle's front yard in southwest Houston and somehow wound up in the Hall of Fame as one of the greatest players in NFL history.

"Sometimes you get so trapped in thinking, 'I'm so busy and doing so many things,' and you kind of go, 'Oh, OK, it's the Hall of Fame,' " Strahan said about being elected in his second year of eligibility. "It's something else that gets added onto the plate. But when you see the response from everybody, it makes you see how big this really is and how much of an honor it is. I'm very excited."

About 50 members of Strahan's family, many from the Houston area, will be at his enshrinement. Some played significant roles in helping him ascend to where he is today - an A-list celebrity who's engaged to Nicole Murphy, ex-wife of Eddie Murphy, and in demand from New York to Los Angeles.

Of family members sitting in the audience in Canton, none will be more proud of Strahan than his mother, father and uncle.

Returning to Houston

Louise and Gene Strahan, who reside in Spring, raised six children, four sons and two daughters.

Gene, a former boxer, was a major in the U.S. Army. Louise, a basketball coach, also was a good athlete. They moved to Germany when Michael was 9.

"When we were in Germany, Michael kind of grew into football," Gene said about his youngest son. "When he was 15, it's like he just popped up overnight."

As Michael grew, Gene started to think about the possibility of his son earning a scholarship to play college football.

"Michael had talent, but I thought it would be wasted if I didn't get him back to Houston," Gene said. "I wanted him to get a season of high school training and see what happened."

Gene had just the person to take in Michael, teach him the game and serve as a father figure - his brother, Arthur Ray Strahan.

Art - or Uncle Ray to family members - played defensive end at TSU as well as for the Oilers and Atlanta Falcons.

"One of the things I kind of questioned was would Michael have the courage to deal with it?" Gene said. "He was easygoing, and his speed and strength - and his courage - were deceptive."

Michael didn't want to leave his parents, but he knew better than to question their authority.

"My dad had told me he thought I was good enough to get a football scholarship," Michael said. "I'd only played football a year (in Germany), but he told me to do it, that I was good at it, and I believed him."

His parents gave him advice before he departed for Houston.

"I hoped he'd remember what we instilled in him and remember what he was going there to do," Louise said. "A lot of kids leave home and get into trouble.

"In a way, Michael had been sheltered. Coming back to the States was cultural shock for him."

Homesick and scared

The plan was for Strahan to move in with Art's family, play a senior season at Westbury in the fall before returning to Germany to graduate from his private academy.

"Man, I was scared to death," Michael said. "I was homesick for my mom and dad. It was extremely tough. Nothing was natural.

"I never thought I could (play high school football). I had to figure it out as I went. I thought I was just a guy on the field to take up space, but it was because of my lack of knowledge more than anything else, and not my desire."

Michael spent a lot of time on the telephone with his parents.

"He'd call us and tell us he was ready to come back home to Germany, and I'd tell him, 'Son, you are home,' " Louise said.

After his one season at Westbury, Strahan returned to Germany to graduate from his private academy - in a class of two - before returning to Houston for good.

Uncle Ray's tough love

The making of Michael Strahan into a football player is a fascinating story about desire, discipline and tough love in his uncle's front yard.

Art Strahan went old school on his nephew.

"My brother thought Michael was too young, but I said, 'Gene, I'll handle him. I won't hurt him mentally or let him get hurt,' " Art said. "I told Michael it was going to be difficult to get an opportunity (for a scholarship), but he'd have a chance if he followed my instructions and stayed out of trouble.

"It was a whole new world for him in America. He was quiet when he wasn't with his family. He was timid. He'd never played (organized) football. I told him, 'Michael, you've got to suck it up. If there's no pain, there's no gain.' "

The uncle and his nephew worked in the summer heat and humidity.

"He was going from one level to another, and I used to get him in my front yard and beat him up just like he was in the NFL," Art said. "I had to make him mentally tough.

"I had to develop an attitude where you had a right to get tired, but you didn't have a right to quit. I didn't want to give him an excuse for failure. I told him, 'Michael, you've got to kill the will of the man across from you because pain don't discriminate.' "

Looking back, Strahan said he never had a coach at any level of competition who was tougher than his uncle.

"I remember Uncle Ray taking me in the front yard and slapping me around and showing me all different kinds of techniques and not taking it easy on me," Michael said. "Without my dad being there, he was like a father to me.

"Seeing him and Aunt Jean on an everyday basis got me through it."

Art takes a lot of pride in what his nephew has achieved on and off the field.

"Michael's the total package, a perfect example of what the NFL represents," Art said. "My pride in what Michael's accomplished can't be put into words. Michael has never forgotten where he came from, and he never will. I'm so thankful that he stands out like a shining star."

On the mantle above his fireplace, Art has a framed, autographed picture of Michael tackling Green Bay quarterback Brett Favre to set the NFL single-season sack record of 22½ in 2001.

"Uncle Ray, thanks for all the lessons in the front yard," Michael wrote. "They have paid off."

But all that hard work resulted in a lone scholarship offer to Cisco Junior College.

Then Strahan's life changed when his uncle took him to TSU to meet coach Walter Highsmith.

Growing up at TSU

Like Art Strahan, Highsmith knew what it took to play in the NFL. He also played for the Oilers, as did three of his assistants - C.L. Whittington, Conway Hayman and Al Johnson.

Highsmith accepted Strahan as a walk-on and placed him at tight end.

"I didn't even have any film on him, but I knew he had good bloodlines," Highsmith said. "I soon realized he wasn't a tight end, that he belonged on the defensive side of the ball, so we moved him.

"Michael was a workaholic, and I worked the hell out of him. He was gifted, and he wanted to be good. The harder he worked and the more he learned about the game, the better he became.

"I told Michael, 'Wherever you go, don't you let anyone outwork you,' and he hasn't. No matter what he's done, he's always wanted to be the best at it."

Strahan worked hard to get a scholarship.

As a junior, he became one of the Southwestern Athletic Conference's best players with 14½ sacks. As a senior, he became one of the best players in the country, posting 32 tackles for loss and 19 sacks.

Strahan is passionate about TSU and appreciative of the role his college played in his development as a player and as a young man. He donated $100,000 to help the school's famed band, the Ocean of Soul, join him in Canton. He has contributed to other fundraising efforts at TSU, and his generosity will continue.

"At TSU, I grew from a boy to a man in a lot of different ways," Strahan said. "I didn't know anything when I got there, and I was around all these guys who were big and tough and strong and fast and grew up playing football. I had to grow up really fast.

"I didn't get swallowed up by the size of the school. I wasn't just a number. I felt like I was a human being. That was important for me getting acclimated to living in the U.S. after being gone for so long."

Strahan helped put together a recent roast of Highsmith, who resides in Alvin.

"He was a tough coach," Strahan said. "He was always pushing you past where you thought you could go, always making you find that next gear to reach that next level.

"That made it easier for me once I got to the Giants. I'd been pushed as hard as I could be pushed, and I knew I wouldn't crack under pressure."

Induction excitement

Washington Redskins senior vice president of communications Tony Wyllie, a Houston native who worked for the Texans, was a classmate of Strahan's at TSU. They have been friends since they met on campus.

"The whole campus is buzzing about his induction," Wyllie said. "He loves TSU and does so much for the school."

The Strahans had a draft party at Art's house in 1993. Family members, friends and media were invited.

"I remember the night before the draft when I ran into Michael at a 7-11," Wyllie said. "It was a funny scene watching him stuff himself into a green Ford Fiesta.

"You know, I'm pretty sure that's the last time he owned a tiny car like that."

Now Strahan can afford any kind of car he wants and as many as he wants.

"He comes from very humble means, and he's reached the pinnacle of success," Art Strahan said. "He sets an example that if you do it the right way, success can be beating down your door."

This post was written by sports